Pg. 501

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 June 18, 1853.]

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 501

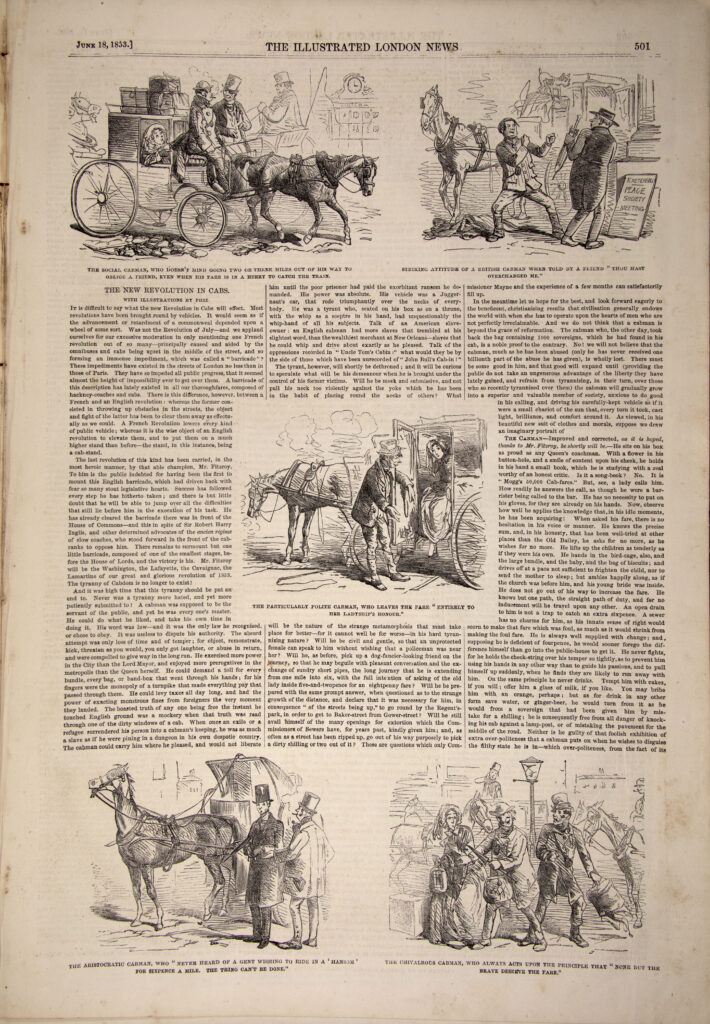

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 THE SOCIAL CABMAN, WHO DOESN’T MIND GOING TWO OK THREE MILES OUT OF HIS WAY TO OBLIGE A FRIEND, EVEN WHEN DIS FARE IS IN A HURRY TO CATCH THE TRAIN.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 STRIKING ATTITUDE OF A BRITISH CABMAN WHEN TOLD BY A FRIEND “ THOU HAST OVERCHARGED ME.”

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 missioner Mayne and the experience of a few months can satisfactorily fill up.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 1 doing it. His word was law—and it was the only law he recognised, or chose to obey. It was useless to dispute his authority. The absurd attempt was only loss of time and of temper; for object, remonstrate, kick, threaten as you would, you only got laughter, or abuse in return, and were compelled to give way in the long run. He exercised more power in the City than the Lord Mayor, and enjoyed more prerogatives in the metropolis than the Queen herself. He could demand a toll for every bundle, every bag, or band-box that went through his hands; for his fingers were the monopoly of a turnpike that made everything pay that massed through them. He could levy taxes all day long, and had the power of exacting monstrous fines from foreigners the very moment hey landed. The boasted truth of any one being free the instant he touched English ground was a mockery when that truth was read through one of the dirty windows of a cab. When once an exile or a refugee surrendered his person into a cabman’s keeping, he was as much slave as if he were pining in a dungeon in his own despotic country, he cabman could carry him where he pleased, and would not liberate

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 THE NEW REVOLUTION IN CABS.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY PHIZ.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 1 It is difficult to say what the new Revolution in Cabs will effect. Most revolutions have been brought round by vehicles. It would seem as if the advancement or retardment of a commonweal depended upon a wheel of some sort. Was not the Revolution of July—and we applaud ourselves for our excessive moderation in only mentioning one French revolution out of so many—principally caused and. aided by the omnibuses and cabs being upset in the middle of the street, and so forming an immense impediment, which was called a “ barricade ” ? These impediments have existed in the streets of London no less than in those of Paris. They have so impeded all public progress, that it seemed almost the height of impossibility ever to get over them. A barricade of this description has lately existed in all our thoroughfares, composed of hackney-coaches and cabs. There is this difference, however, between a French and an English revolution: whereas the former consisted in throwing up obstacles in the streets, the object and fight of the latter has been to clear them away as effectually as we could. A French Revolution lowers every kind of public vehicle; whereas it is the wise object of an English revolution to elevate them, and to put them on a much higher stand than before—-the stand, in this instance, being a cab-stand.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 1 The last revolution of this kind has been carried, in the most heroic manner, by that able champion, Mr. Fitzroy. To him is the public indebted for having been the first to mount this English barricade, which had driven back with fear so many stout legislative hearts. Success has followed every step he has hitherto taken; and there is but little doubt that he will be able to jump over all the difficulties that still lie before him in the execution of his task. He has already cleared the barricade there was in front of the House of Commons—and this in spite of Sir Robert Harry Inglis, and other determined advocates of the ancien regime of slow coaches, who stood forward in the front of the cabranks to oppose him. There remains to surmount but one little barricade, composed of one of the smallest stages, before the House of Lords, and the victory is his. Mr. Fitzroy will be the Washington, the Lafayette, the Cavaignac, the Lamartine of our great and glorious revolution of 1853. The tyranny of Cabdom is no longer to exist!

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 And it was high time that this tyranny should be put an end to. Never was a tyranny more hated, and yet more patiently submitted to ! A cabman was supposed to be the servant of the public, and yet he was every one’s master. He could do what he liked, and take his own time in

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 1 him until the poor prisoner had paid the exorbitant ransom he demanded. His power was absolute. His vehicle was a Juggernaut’s car, that rode triumphantly over the necks of everybody. He was a tyrant who, seated on his box as on a throne, with the whip as a sceptre in his hand, had unquestionably the whip-hand of all his subjects. Talk of an American slaveowner : an English cabman had more slaves that trembled at his slightest word, than the wealthiest merchant at New Orleans—slaves that he could whip and drive about exactly as he pleased. Talk of the oppressions recorded in “ Uncle Tom’s Cabin:” what would they be by the side of those which have been unrecorded of “John Bull’s Cab-in ! ”

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 The tyrant, however, will shortly be dethroned ; and it will be curious to speculate what will be his demeanour when he is brought under the control of his former victims. Will he be meek and submissive, and not pull his neck too violently against the yoke which he has been in the habit of placing round the necks of others ? What

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 will be the nature of the strange metamorphosis that must take place for better—for it cannot well be for worse—in his hard tyrannizing nature ? Will he be civil and gentle, so that an unprotected female can speak to him without wishing that a policeman was near her ? Will he, as before, pick up a dog-fancier-looking friend on the journey, so that he may beguile with pleasant conversation and the exchange of sundry short pipes, the long journey that he is extending from one mile into six, with the full intention of asking of the old lady inside five-and-twopence for an eightpenny fare ? Will he be prepared with the same prompt answer, when questioned as to the strange growth of the distance, and declare that it was necessary for him, in consequence “ of the streets being up,” to go round by the Regent’s- park, in order to get to Baker-street from Gower-street ? Will he still avail himself of the many openings for extortion which the Commissioners of Sewers have, for years past, kindly given him; and, as often as a street has been ripped up, go out of his way purposely to pick a dirty shilling or two out of it ? These are questions which only Com-

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 In the meantime let us hope for the best, and look forward eagerly to the beneficent, christianising results that civilisation generally endows the world with when she has to operate upon the hearts of men who are not perfectly irreclaimable. And we do not think that a cabman is beyond the grace of reformation. The cabman who, the other day, took back the bag containing 1000 sovereigns, which he had found in his cab, is a noble proof to the contrary. No! we will not believe that the cabman, much as he has been abused (only he has never received one billionth part of the abuse he has given), is wholly lost. There must be some good in him, and that good will expand until (providing the public do not take an ungenerous advantage of the liberty they have lately gained, and refrain from tyrannising, in their turn, over those who so recently tyrannised over them) the cabman will gradually grow into a superior and valuable member of society, anxious to do good in his calling, and driving his carefully-kept vehicle as if it were a small chariot of the sun that, every turn it took, cast light, brilliance, and comfort around it. As viewed, in his beautiful new suit of clothes and morals, suppose we draw an imaginary portrait of

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 The Cabman—Improved and corrected, as it is hoped, thanks to Mr. Fitzroy, he shortly will be.—He sits on his box as proud as any Queen’s coachman. With a flower in his button-hole, and a smile of content upon his cheek, he holds in his hand a small book, which he is studying with a zeal worthy of an honest critic. Is it a song-book ? No. It is “ Mogg’s 50,000 Cab-fares.” But, see, a lady calls him. How readily he answers the call, as though he were a barrister being called to the bar. He has no necessity to put on his gloves, for they are already on his hands. Now, observe how well he applies the knowledge that, in his idle moments, he has been acquiring ! When asked his fare, there is no hesitation in his voice or manner. He knows the precise sum, and, in his honesty, that has been well-tried at other places than the Old Bailey, he asks for no more, as he wishes for no more. He lifts up the children as tenderly as if they were his own. He hands in the bird-cage, also, and the large bundle, and the baby, and the bag of biscuits; and drives off at a pace not sufficient to frighten the child, nor to send the mother to sleep; but ambles happily along, as if the church was before him, and his young bride was inside. He does not go out of his way to increase the fare. He knows but one path, the straight path of duty, and for no inducement will he travel upon any other. An open drain to him is not a trap to catch an extra sixpence. A sewer has no charms for him, as his innate sense of right would

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 scorn to make that fare which was foul, as much as it would shrink from making the foul fare. He is always well supplied with change; and, supposing he is deficient of fourpence, he would sooner forego the difference himself than go into the public-house to get it. He never fights, for he holds the check-string over his temper so tightly, as to prevent him using his hands in any other way than to guide his passions, and to pull himself up suddenly, when he finds they are likely to run away with him. On the same principle he never drinks. Tempt him with cakes, if you will; offer him a glass of milk, if you like. You may bribe him with an orange, perhaps; but as for drink in any other form save water, or ginger-beer, he would turn from it as he would from a sovereign that had been given him by mistake for a shilling; he is consequently free from all danger of knocking his cab against a lamp-post, or of mistaking the pavement for the middle of the road. Neither is he guilty of that foolish exhibition of extra over-politeness that a cabman puts on when he wishes to disguise the filthy state he is in—which over-politeness, from the fact of its

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 THE PARTICULARLY POLITE CABMAN, WHO LEAVES THE FARE U ENTIRELY TO HER LADYSHIP’S HONOUR.”

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 THE ARISTOCRATIC CABMAN, WHO ” NEVER HEARD OF A GENT WISHING TO RIDE IN A ‘ HANSOM ’

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 FOR SIXPENCE A MILE. THE THING CAN’T BE DONE.”

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 THE CHIVALROUS CABMAN, WHO ALWAYS ACTS UPON THE PRINCIPLE THAT “ NONE BUT THE BRAVE DESERVE THE FARE.”

cabman: the driver of a horse-drawn hackney carriage

source: Oxford Dictionary